This

post was originally published on

this siteOriginally Posted At: https://breakingmuscle.com/feed/rss

The glute bridge and hip thrust are assistance exercises often used in an effort to strengthen the glutes for the squat. They are also utilized in the world of rehabilitation for “underactive” glutes.

The aim of this article is to break down the functional mechanics of the bridge in comparison to the squat, and explain how it’s possible to train the bridge, yet still be unable to recruit the glutes during the squat.

(From now on I will use “bridge” to cover the use of both the glute bridge and hip thrust).

How the Muscles Work

Before we analyze the squat and the bridge, we must begin with principles that allow us to understand how muscles function in an isolated exercise like the bridge versus the compound movement of the squat.

“The bridge has a high EMG activity; therefore, it should teach our glutes to work when we perform the more functional, compound squat. So why doesn’t this happen?”

A lot of exercise science concerns strengthening muscles in an isolated way. This isolated method is based upon a concentric muscular contraction that shortens and creates motion. In the case of the bridge, the glute concentrically contracts to produce hip extension.

In an article called Hip Thrust and Glute Science, Bret Contreras discussed the science of maximally recruiting the glutes, including a study on the optimal amounts of hip and knee flexion required for the greatest EMG readings. The purpose of this article is not to question his methods, as they are correct for the function and goal for which they are used – maximum glute contraction for maximal hypertrophic gains. Instead, this article will show how the bridge is not correct for improving glute function in our goal, the squat.

The glute bridge has been supposedly developed further with the use of bands around the knees to push out against (hip abduction) and turning the toes (external rotation). The theory is that performing all three concentric glute muscle actions simultaneously (extension, abduction, external rotation) will ensure maximum EMG activity of the glute.

“Conscious muscle contractions come from isolated movements, but during functional (multi-jointed) movement it is impossible to tell every muscle to work.”

A high EMG reading is considered of great importance in terms of how good an exercise is at recruiting a muscle. The bridge has a high EMG activity; therefore, it should teach our glutes to work when we perform the more functional, compound squat.

So why doesn’t this happen?

How the Body Works

In the bridge, you aren’t teaching the glute to squat, but only to hip extend. The bridge works in the lying face-up position, with a nervous system that is as good as asleep. Relate this to prolonged bed rest, where muscles atrophy and people get weaker because we have lost our fight against gravity, which is the thing that stimulates low-grade constant muscle activation.

When we lie down, we are no longer fighting gravity. This means the nervous system throughout the body is experiencing little to no activation. So when the hips are driven upward, the only neurological drive goes to the glutes, hence the high EMG reading for the bridge.

When we stand under load ready to squat, the amount of pressure the whole nervous system experiences is greater than that of the bridge. As we begin our descent and the hips are moving toward the floor, there is neurological activity going to every muscle of the body. As we squat, muscles within the hip are all shortening and lengthening at different times, learning how to work as a team to overcome both gravity and the load that is traveling with momentum.

This is one of the key factors as to why the glute bridge doesn’t transfer to squatting. The body works as one complete system, with a huge neurological conversation going on between the muscles to complete the task. When we perform a glute bridge, the glutes are learning to work in isolation, and there is little conversation with neighboring muscular friends. Consequently, when we stand up and perform a squat, the glutes no longer know when they need to contract relative to the other muscles working during the compound squatting movement.

“When we perform a glute bridge, the glutes are learning to work in isolation, and there is little conversation with neighbouring muscular friends.”

The nervous system works subconsciously to control all human movement. Conscious muscle contractions come from isolated movements, but during functional (multi-jointed) movement it is impossible to tell every muscle to work. You can’t choose the sequencing of muscle firing patterns because there is more than one muscle working. It is impossible to consciously control the complexity of that sequencing. Even if you could control the sequencing, you would be so distracted from the task at hand that you would probably fail the lift anyway.

How the Mechanics Work

The sequencing of muscles is not the only contrasting factor, the mechanics are also different. In the bridge, the glute is starting from a point of no activity and then shortening. The glute has stored energy, but there is no stretch-shortening cycle like there is in the squat.

During the down phase of the squat, the glute is moving through hip flexion, adduction (it starts in a relatively abducted position, but continues to move inward as you squat), and internal rotation. These are the natural mechanics of the squat descent.

The coupled mechanics of the knee are flexion and internal rotation, so an internally rotating femur occurs in the eccentric phase of the squat. Please note, I am not saying the knees kiss each other. If the knee tracks over the foot, then this is internal rotation of the hip.

The down phase creates a lengthening of the glute in all three planes motion (hip flexion in the sagittal plane, hip adduction in the frontal plane, and internal rotation in the transverse plane). This lengthening process creates an elastic load that enables the glute to explosively and concentrically extend, abduct, and externally rotate the hip, allowing us to stand.

“[L]imited range of motion means the glute isn’t learning what to do in the hole at the bottom of the squat, which is when we really need the glute to help us.”

The above joint motions are not replicated during a bridge, as there is no stretch-shortening occurring due to the limited range of motion the bridge is performed within. One effect of the bridge is glute tightness, meaning the glute can only contract in a shortened range of motion, not in a huge range of motion like the squat. This limited range of motion means the glute isn’t learning what to do in the hole at the bottom of the squat, which is when we really need the glute to help us.

Enter the Lunge

To truly assist the activation of the glute, the closest exercise to the squat is the lunge. The joint motions of the hip are almost identical – hip flexion, internal rotation, and adduction on the descent of movement, allowing the glute to work through its stretch-shortening cycle. However, there is a small difference between the squat and the lunge. In the lunge, we have ground reaction force as the foot hits the floor, so the mechanics are not fully identical as the squat has a top-down loading pattern.

But in the lunge the glute is learning how to work with all the other muscles of the hip in a coordinated and synchronized sequence of movement. The joint angles are similar to that of the squat (on the front leg) and, importantly, the ankle, knee and spine are learning how to move with the hips through that motion as well. In the bridge, only the hip is moving and extending, with the ankle and spine in a completely different position and under a different stress than in the squat, so the correct movement pattern and muscle sequence is not being learned.

“In the bridge, only the hip is moving and extending, with the ankle and spine in a completely different position and under a different stress than in the squat.”

The lunge also allows each leg to work independently and get strong in its own right. I have yet to assess a squat that is 100% balanced. We all have a leg that is stronger and that we favor when we squat. We must try and balance the system.

So, go forth and lunge! But doing thirty lunges is not enough to create desired changes to motor pattern recruitment. Part two of this article will delve into the programming required to make significant changes to your motor patterns.

You’ll also find these articles interesting:

References:

1. Contreras, B. “Hip Thrust and Glute Science.” The Glute Guy. Last modified April 6, 2013.

2.Worrell TW., et al. “Influence of joint position on electromyographic and torque generation during maximal voluntary isometric contractions of the hamstrings and gluteus maximus muscles.” J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2001 Dec;31(12):730-40.

Photo 1 courtesy ofShutterstock.

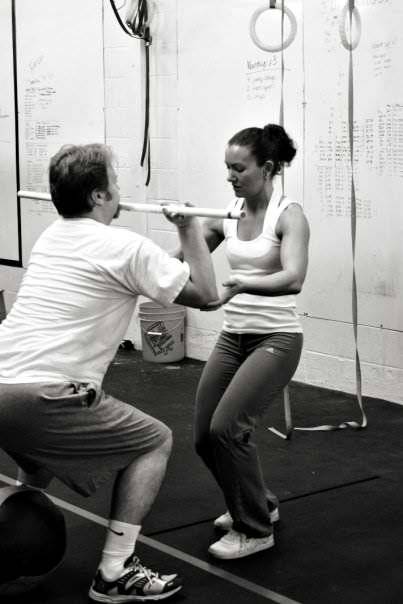

Photo 2, 3, & 4 courtesy ofCrossFit Empirical.

The post Why Doing Glute Bridges Will Never Help Your Squat appeared first on Breaking Muscle.

More recently, when I teach or coach, the concepts of the ZPD and the more knowledgeable/capable other have helped me understand that sometimes I may be asking too much of someone, even if I believe I am effectively

More recently, when I teach or coach, the concepts of the ZPD and the more knowledgeable/capable other have helped me understand that sometimes I may be asking too much of someone, even if I believe I am effectively  Mashed potatoes are almost expected as part of a holiday spread. In fact, I would argue that mashed potatoes appear on more holiday tables than a

Mashed potatoes are almost expected as part of a holiday spread. In fact, I would argue that mashed potatoes appear on more holiday tables than a

Research of the Week

Research of the Week

If the hidden curriculum reinforces the overt goals of the team, it could be a good thing. On the other hand, if the hidden curriculum undermines or detracts from these goals, disruption can result. As coaches, we must be aware of the existence of these more covert dynamics as well as the effect they may have on our coaching and our athletes’ behavior and mindsets.

If the hidden curriculum reinforces the overt goals of the team, it could be a good thing. On the other hand, if the hidden curriculum undermines or detracts from these goals, disruption can result. As coaches, we must be aware of the existence of these more covert dynamics as well as the effect they may have on our coaching and our athletes’ behavior and mindsets. I never got to do a kickboxing match and I have lingering back problems to this day. But I might never have become a coach if I hadn’t overtrained myself into a pulp. I wouldn’t trade my career as a coach for being pain free any day. And, as I mentioned earlier, I also earned the gift of being able to spot the stupid a mile away. I know who you are, you overtrainers – I know you inside and out. And ever since those tough, dark times I’ve made a mission of reaching out to those on that same path, so maybe they won’t go quite so far down the rabbit hole as I did.

I never got to do a kickboxing match and I have lingering back problems to this day. But I might never have become a coach if I hadn’t overtrained myself into a pulp. I wouldn’t trade my career as a coach for being pain free any day. And, as I mentioned earlier, I also earned the gift of being able to spot the stupid a mile away. I know who you are, you overtrainers – I know you inside and out. And ever since those tough, dark times I’ve made a mission of reaching out to those on that same path, so maybe they won’t go quite so far down the rabbit hole as I did. I remember standing there mid-workout, looking at the bar, looking at the rubber band, and then saying out loud, “I don’t remember it being this hard.” Andy Petranek looked over at me and said, “What, pull ups?” And I said, “No, CrossFit.”

I remember standing there mid-workout, looking at the bar, looking at the rubber band, and then saying out loud, “I don’t remember it being this hard.” Andy Petranek looked over at me and said, “What, pull ups?” And I said, “No, CrossFit.” For now classes are 6pm and 640pm at 2840 Wildwood st in the Boise Cloggers studio.

Book your class NOW!

click this ==>

For now classes are 6pm and 640pm at 2840 Wildwood st in the Boise Cloggers studio.

Book your class NOW!

click this ==>